We are the stories we tell.

That is what I tell my high school students.

Not in an abstract, Shakespearean sort of way. I mean it literally: you are the product of your stories. Your background, your childhood, your traumas, your joys, your cultural heritage, your experience-informed preferences and habits. Your past is a collection of stories, and those stories have molded you into the person you are today.

This is why I encourage others to examine the content they absorb. Last year, I noted how media impacts our views of the world:

I was reminded recently that there is no such thing as mindless scrolling or viewing. Our brains absorb everything we put in front of our eyes, even if it happens in ways we don’t comprehend. So it makes sense that we should analyze the types of media we experience. If the movies and shows I watch impact my perception of the world, I should examine which movies and shows I experience.

But this year, I want to expand on that thesis: the content we experience impacts our perceptions of ourselves as well as our world. Stories are powerful. They can subtly change how we frame our own experiences and alter how we process our own thoughts. If you tell yourself a story often enough, that story becomes indistinguishable from truth. This phenomenon can be powerful or terrifying, depending on the story.

With that in mind, below is an analysis of every movie, television show, video game, and feature-length YouTube video I experienced for the first time in 2025. The data is first, then an analysis, and then a comprehensive list of everything I experienced.

The Data

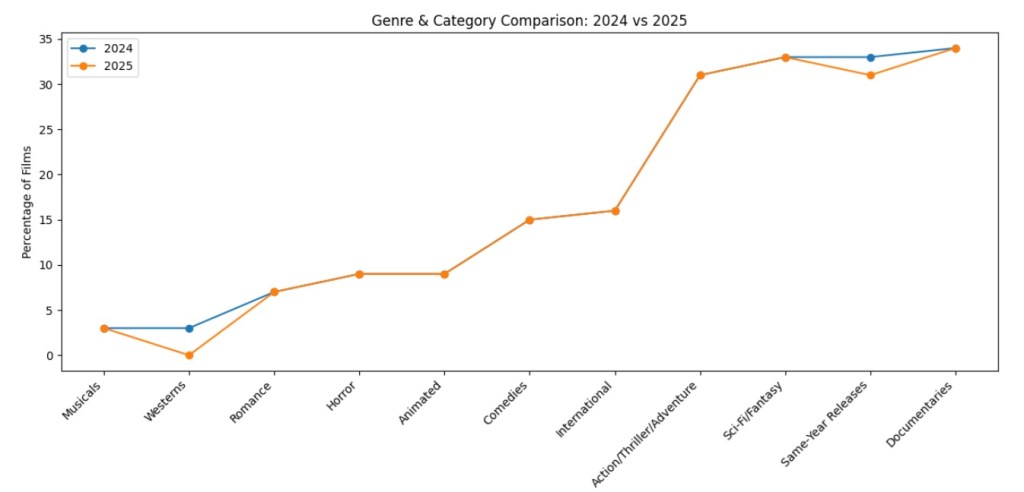

Of the films I watched for the first time in 2025:

- 0% are Westerns

- 7% are mysteries

- 7% are romance films

- 9% are horror films

- 9% are animated films

- 15% are comedies

- 31% are action, thriller, or adventure films

- 33% are science fiction or fantasy

- 31% are films that released in 2025

- 34% are documentaries

- ~58% are dramas

Of the television show seasons I watched for the first time in 2025:

- ~6% are reality television

- ~8% are historical dramas or comedies

- ~14% are animated

- ~17% are science fiction or fantasy

- ~28% are comedies

- ~31% are dramas (not reality television)

Analysis

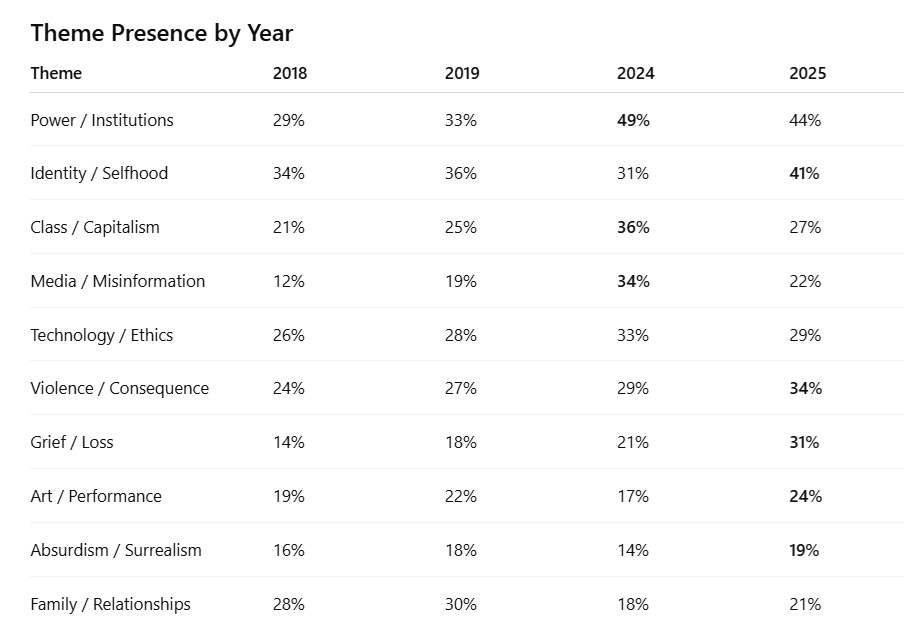

Commentary on Power: I have taught George Orwell’s 1984 more frequently than most any other story. (It is second only to William Shakespeare’s Macbeth.) While we read Orwell’s classic dystopian tale, my students explore the three laws of power: 1) power is never static, 2) power flows through everyday life like water, and 3) power creates opportunities for more power, as TED-ed’s Eric Liu explains. In every scenario, you are either exerting your influence on others, or others are exerting their influence on you. This is why conversations about power are so important: we need to understand the ubiquity of daily power dynamics in order to challenge manipulative, toxic, or dangerous uses of power. I am not sure exactly why my recent film viewing experiences incorporate themes of power and ethics so frequently, but I imagine it has something to do with my continued belief in the value of identifying the intangible-yet-powerful power dynamics in our day-to-day lives. Some of my favorite cinematic explorations of power: Prime Minister (2025), Lilith Fair: Building a Mystery (2025), Join or Die (2023), This Place Rules (2022), and Pariyerum Perumal (2018).

Consistency Is Key(?): Apparently, my film viewing habits are bewilderingly consistent. In regard to genre, my 2025 viewing statistics are nearly identical to my 2024 stats. On one hand, this speaks to the sincerity with which I pursue documentaries and science fiction. My love of knowledge and fantasy is a consistent part of my identity, apparently. On the other hand, I worry that I have stagnated as a moviegoer. In 2024, for example, I explained that I had recently discovered an appreciation for Westerns, yet I did nothing to nurture that appreciation in 2025. Should I consciously pick more romance, horror, and animated films in 2026? Maybe. Or maybe it’s okay that I like what I like. Genre does not determine quality. Either way, I would like to expand my awareness of international, non-U.S. films. That is a worthy goal, and it is my goal for 2026.

Other Observations and Subjective Awards

Movies

Favorite movies released in 2025: 28 Years Later, Bison Kaalamaadan, O’Dessa, Prime Minister, Steve

Favorite pre-2025 films I watched: Nayakan (1987), Panchatanthiram (2002), Pariyerum Perumal (2018), A Real Pain (2024), I’m Still Here (2024), Sonic the Hedgehog 3 (2024), Nickel Boys (2024), Anora (2024)

Film maudit (films “unfairly maligned” by critics): O’Dessa (2025)—39% on Rotten Tomatoes, 2.5 on Letterboxd, and 5/10 on IMDb, but I absolutely love this film. Highly recommend.

Most-watched director in 2025: Mari Selvaraj (Pariyerum Perumal, Vaazhai, and Bison Kaalamaadan)

Movies I started with no expectations and found surprisingly good: Dave Made a Maze (2017), Pig (2021), Join or Die (2023), Wicked Little Letters (2023), On Falling (2024), Sonic the Hedgehog 3 (2024), Jazzy (2024), O’Dessa (2025)

Movies I started with mid-to-high expectations and found notably disappointing: A Complete Unknown (2024), Sacramento (2024), Tron: Ares (2025), Mountainhead (2025)

Worst movies watched in 2025: Captain America: Brave New World (2025), Trainwreck: Balloon Boy (2025)

Television Shows

Favorite shows and seasons: The Pitt (S1), Andor (S2), Barry (S1, S2), Grey’s Anatomy (S2), American Primeval (S1), Victoria (S2, S3)

New recipient of my Near-Perfect Show award: Andor. Only two other shows have received this honor: Succession and BoJack Horseman.

Seasons that were almost brilliant but not quite there: Search Party (S1, S2, S3), The Last of Us (S2)

Not blown away but will probably continue watching: Shadow and Bone and Star Trek: Strange New Worlds

Seasons that were better than most people think: The Witcher (S4)

Disappointing seasons: Mythic Quest (S4), The Sandman (S2)

Video Games

Favorite game beat in 2025: Atomfall

Games that were surprisingly enjoyable: A Way Out and Grounded

Games with the best music: NieR: Automata and The Outer Worlds 2

Games that were aggressively mediocre (not unpleasant, but not great): Super Mario Bros. Wonder, Assassin’s Creed: Origins, and Far Cry New Dawn

YouTube

Most-watched creators in 2025: Willjum, Simon Wilson, Channel 5 with Andrew Callaghan, DougDoug, and JGigs

Best videos: “Dua Lipa versus the literary landscape” by Below the Fray, “The Godawful Presidents of the Marvel Cinematic Universe” by Nando v Movies, “Overnight on Moldova’s Worst Sleeper Train” by Simon Wilson, “The Absolute Chaos of Bethesda” by big boss, “Is Gen Z ‘Too Woke’ Or Are You Just Too Dumb? (the rise of anti-intellectualism)” by imuRgency, and “The Hardest Soulslike” by videogamedunkey

LIST OF FILMS WATCHED FOR THE FIRST TIME IN 2025

Bullet Train (2022) dir. David Leitch

A Scanner Darkly (2006) dir. Richard Linklater

Mystery Men (1999) dir. Kinka Usher

Gladiator II (2024) dir. Ridley Scott

Society of the Snow (2023) dir. J. A. Bayona

Tollbooth (2021) dir. Ryan Andrew Hooper

This Place Rules (2022) dir. Andrew Callaghan

Alien: Romulus (2024) dir. Fede Álvarez

Venom: The Last Dance (2024) dir. Kelly Marcel

Sonic the Hedgehog 3 (2024) dir. Jeff Fowler

A Real Pain (2024) dir. Jesse Eisenberg

I’m Still Here (2024) dir. Walter Salles

Nickel Boys (2024) dir. RaMell Ross

Anora (2024) dir. Sean Baker

The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017) dir. Yorgos Lanthimos

The Founder (2016) dir. John Lee Hancock

Ghosts of the Deep: Black Sea Shipwrecks (2019) dir. David Belton, Andy Byatt

In the Heights (2021) dir. Jon M. Chu

The Fallout (2021) dir. Megan Park

I’m Totally Fine (2022) dir. Brandon Dermer

Flow (2024) dir. Gints Zilbalodis

The Electric State (2025) dir. Anthony Russo, Joe Russo

The Monkey King: Reborn (2021) dir. Wang Yunfei

O’Dessa (2025) dir. Geremy Jasper

A Complete Unknown (2024) dir. James Mangold

Dave Made a Maze (2017) dir. Bill Watterson

Last Exit: Space (2022) dir. Rudolph Herzog

The Perfect Weapon (2020) dir. John Maggio

Tuesday (2023) dir. Daina O. Pusić

Mickey 17 (2025) dir. Bong Joon Ho

The Pale Blue Eye (2022) dir. Scott Cooper

Ballet Now (2018) dir. Steven Cantor

Britain and the Blitz (2025) dir. Ella Wright

King Lear (2018) dir. Richard Eyre

A Brief History of Time (1991) dir. Errol Morris

Parthenope (2024) dir. Paolo Sorrentino

Captain America: Brave New World (2025) dir. Julius Onah

The Order (2024) dir. Justin Kurzel

Seven Veils (2023) dir. Atom Egoyan

Thunderbolts* (2025) dir. Jake Schreier

The Wild Robot (2024) dir. Chris Sanders

Join or Die (2023) dir. Pete Davis, Rebecca Davis

Biggest Heist Ever (2024) dir. Chris Smith

Mountainhead (2025) dir. Jesse Armstrong

Pete’s Dragon (2016) dir. David Lowery

Rosetta (1999) dir. Luc Dardenne, Jean-Pierre Dardenne

Valley of the Dead (2020) dir. Alberto de Toro, Javier Ruiz Caldera

Shock and Awe (2017) dir. Rob Reiner

Jazzy (2024) dir. Morrisa Maltz

West Side Story (2021) dir. Steven Spielberg

Scoop (2024) dir. Philip Martin

Ballerina (2025) dir. Len Wiseman

Power (2024) dir. Yance Ford

Nayakan (1987) dir. Mani Ratnam

Pig (2021) dir. Michael Sarnoski

Blink Twice (2024) dir. Zoë Kravitz

A Minecraft Movie (2025) dir. Jared Hess

CTRL (2024) dir. Vikramaditya Motwane

Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning (2025) dir. Christopher McQuarrie

28 Years Later (2025) dir. Danny Boyle

Hotel Transylvania 2 (2015) dir. Genndy Tartakovsky

Hotel Transylvania (2012) dir. Genndy Tartakovsky

Going Down (1982) dir. Haydn Keenan

F1 The Movie (2025) dir. Joseph Kosinski

How to Train Your Dragon (2025) dir. Dean DeBlois

On Falling (2024) dir. Laura Carreira

Maharaja (2024) dir. Nithilan Saminathan

The Ron Clark Story (2006) dir. Randa Haines

The Fantastic Four: First Steps (2025) dir. Matt Shakman

Superman (2025) dir. James Gunn

Uncharted (2022) dir. Ruben Fleischer

Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998) dir. Karan Johar

Trainwreck: Poop Cruise (2025) dir. James Ross

Trainwreck: The Cult of American Apparel (2025) dir. Sally Rose Griffiths

Unknown Number: The High School Catfish (2025) dir. Skye Borgman

Bulbul Can Sing (2018) dir. Rima Das

Pariyerum Perumal (2018) dir. Mari Selvaraj

Trainwreck: The Real Project X (2025) dir. Alex Wood

Death of a Unicorn (2025) dir. Alex Scharfman

Friendship (2024) dir. Andrew DeYoung

Superman: Man of Tomorrow (2020) dir. Chris Palmer

Sacramento (2024) dir. Michael Angarano

Kaithi (2019) dir. Lokesh Kanagaraj

Surviving Ohio State (2025) dir. Eva Orner

Superman: Unbound (2013) dir. James Tucker

Vaazhai (2024) dir. Mari Selvaraj

Elio (2025) dir. Adrian Molina, Domee Shi, Madeline Sharafian

Daddio (2023) Christy Hall

Prime Minister (2025) dir. Michelle Walshe, Lindsay Utz

Tron: Ares (2025) dir. Joachim Rønning

Lilith Fair: Building a Mystery (2025) dir. Ally Pankiw

Bison Kaalamaadan (2025) dir Mari Selvaraj

Peter Hujar’s Day (2025) dir Ira Sachs

Enthiran (2010) dir. S. Shankar

Steve (2025) dir. Tim Mielants

Diary of a Wimpy Kid Christmas: Cabin Fever (2023) dir. Luke Cormican

The Santa Clause 2 (2002) dir. Michael Lembeck

Thoughts & Prayers: Or How to Survive an Active Shooter in America (2025) dir. Zackary Canepari, Jessica Dimmock

Creep (2014) dir. Patrick Brice

Caught Stealing (2025) dir. Darren Aronofsky

Meiyazhagan (2024) dir. C. Prem Kumar

Holy Motors (2012) dir. Leos Carax

This Place (2022) dir. V.T. Nayani

Home Alone 4 (2002) dir. Rod Daniel

Vikram Vedha (2022) dir. Pushkar–Gayathri

Vada Chennai (2018) dir. Vetrimaaran

Wake Up Dead Man (2025) dir. Rian Johnson

Panchatanthiram (2002) dir. KS Ravikumar

The Bad Guys 2 (2025) dir. Pierre Perifel

Murder in Monaco (2025) dir. Hodges Usry

Trainwreck: Mayor of Mayhem (2025) dir. Shianne Brown

Trainwreck: The Astroworld Tragedy (2025) dir. Yemi Bamiro, Hannah Poulter

Trainwreck: Balloon Boy (2025) dir. Gillian Pachter

Wicked Little Letters (2023) dir. Thea Sharrock

LIST OF TV SHOW SEASONS WATCHED FOR THE FIRST TIME IN 2025

Creature Commandos, S1

Archer, S9

Make Some Noise, S3

Invincible, S3

The White Lotus, S3

Barry, S1, S2, S3

Mythic Quest, S4

Search Party, S1, S2, S3

The Pitt, S1

The Last of Us, S2

Survivor, S48

The Terror, S1

Andor, S2

Star Trek: Strange New Worlds, S1

Rick and Morty, S8

Star Trek: Lower Decks, S5

Tires, S2

Castlevania: Nocturne, S2

The Sandman, S2

Grey’s Anatomy, S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6

Shadow and Bone, S1

The Bear, S1

Peacemaker, S2

Gen V, S2

Death by Lightning, S1

Victoria, S2, S3

All Her Fault, S1

The Witcher, S4

American Primeval, S1

LIST OF VIDEO GAMES BEAT IN 2025

A Way Out (Xbox) – beat: played as Leo; survived

Escape Academy (Xbox) – beat: heart rate increased throughout

Super Mario Bros. Wonder (Nintendo Switch) – beat

NieR: Automata (Xbox) – beat: Become as Gods Edition; Ending A

It Takes Two (Xbox) – beat: played as Cody

Diablo IV (Xbox) – beat: played as a necromancer; lots of reaping

Far Cry New Dawn (Xbox) – beat: spared Mickey (because she was super cool); killed Joseph Seed (obviously)

The Dark Pictures Anthology: Little Hope (Xbox) – beat: saved Andrew, saved Mary

Atomfall (Xbox) – beat: killed Oberon; escaped via the Voice on the Telephone

Grounded (Xbox) – “beat” i.e. made a spectacular grass-based mansion with James

Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic (Xbox) – beat: go-to companions Jolee Bindo, Juhani, and Zaalbar

Assassin’s Creed: Origins (Xbox) – beat

Far Cry 4 (Xbox) – beat: sided with Amita (because Sabal was sexist); killed Pagan

The Outer Worlds 2 (Xbox) – beat: saved Fairfield; spared Seer Wiley; released skip-drive schematics to public; brokered an alliance between Auntie’s Choice and the Order; spared the Consul; go-to companions Niles and Marisol

Dragon Age: The Veilguard (Xbox) – beat: prioritized Treviso; encouraged Emmrich to become a lich; convinced Solas to bond himself to the Veil; Davrin died; go-to companions Lucanis, Emmrich, and Neve

YOUTUBE VIDEOS (VIDEOS & VIDEO ESSAYS OVER 45 MINUTES AND/OR OF NOTABLE QUALITY) WATCHED IN 2025

“Ranking Every Superhero Suit Up Ever” by Y Reviews

“I Played Every Spider-Man Game Ever Made” by Jacko

“I created 100 apartments on one lot…” by James Turner

“These Are The 8 Greatest & Best City Builders Of All Time” by GamerZakh

“Dubai Is Everything Wrong With Society” by Moon

“RFK Jr. Rally” by Channel 5 with Andrew Callaghan

“D.A.R.E. Conference” by Channel 5 with Andrew Callaghan

“Defend the Border Convoy” by Channel 5 with Andrew Callaghan

“The Second Punic War – Oversimplified (Part 3)” by Oversimplified

“Free Luigi Rally” by Channel 5 with Andrew Callaghan

“Poor People’s Army (DNC)” by Channel 5 with Andrew Callaghan

“Why Do Evangelicals Fall For Conspiracy Theories?” by Belief It Or Not

“The Worst Kind of Stupid Person” by Kahmal

“The REAL reason behind Andrew Schulz’s rant” by Quddus Gordon

“The Dark World of Megachurches” by James Jani

“Is Gen Z ‘Too Woke’ Or Are You Just Too Dumb? (the rise of anti-intellectualism)” by imuRgency

“Pennsylvania Bigfoot Conference” by Channel 5 with Andrew Callaghan

“They Couldn’t Make This Game Today” by peterspittech

“This Dark Fantasy RPG is a Freudian Nightmare | Demonicon” by Khanlusa

“Still Wakes the Deep is my Personal NIGHTMARE and I Love It” by Khanlusa

“Why Lolita is Impossible to Adapt into Film” by Final Girl Digi

“Dua Lipa versus the literary landscape” by Below the Fray

“What Makes a Performance ‘Oscar Worthy’?” by From The Frame

“Are People Starting To Hate The Savannah Bananas?” by Baseball Doesn’t Exist

“Is Dave Filoni a FRAUD?” by Typoh

“book red flags and the Male Reading Crisis” by Man Carrying Thing

“The Godawful Presidents of the Marvel Cinematic Universe” by Nando v Movies

“Who Can Write Whose Story?” by Below the Fray

“1000 Players Simulate Earth Civilization in Rust 2.0” by FancyOrb

“Rimworld Medieval, 1 Colonist Start… (5 years)” by ambiguousamphibian

“Rimworld, 100% Passion, 0-Skill Run (8 Years)” by ambiguousamphibian

“New York’s Most Wanted Drivers Pt 2” by Tommy G

“Poorest Region of America – What It Really Looks Like” by Peter Santanello

“Rimworld, 1-PAWN ICE SHEET Survival…(5 years)” by ambiguousamphibian

“Sailor, Soldier, & Explorer Rations: Food for the Commoner – Salt Pork” by Townsends

“The Rise and Fall of The New 52 – What Went Wrong?” by Owen Likes Comics

“40 Best Single-Player Games You Simply Must Experience” by gamewise

“I played the new generation of Official Rust…” by Willjum

“Inside Afghanistan Pakistan Border Town” by Simon Wilson

“Cheapest Hotel vs Most Expensive Hotel in Kazakstan” by Simon Wilson

“I Tried a 1-Star Cruise” by Simon Wilson

“I Tried 1-Star Hotels Across Europe” by Simon Wilson

“I Tried America’s 1-Star Hotels” by Simon Wilson

“I Built the most High IQ solo base in Vanilla Rust…” by Willjum

“A Solo’s Rust Odyssey .. II” by Willjum

“I hired a professional builder to play rust” by Willjum

“How long can a Pro Base Builder survive an Endless Siege?” by Willjum

“I designed a new Solo Strategy on Official Rust..” by Willjum

“How a Solo rat with 13,126 Hours plays Official Rust…” by Willjum

“I survived 7 days solo in vanilla Rust…” by Willjum

“When a solo Farmer Hires a PVP GODSQUAD to play Rust…” by Willjum

“I Survived 24 Hours on a stranded Iceberg in Vanilla Rust…” by Willjum

“I Built an Apocalypse Settlement in Vanilla Rust..” by Willjum

“Two Solos 100 Hour Rust Odyssey…” by Willjum

“I Discovered the New Broken Solo meta for Official Rust…” by Willjum

“I Built the first Invisible jungle stronghold in Official Rust…” by Willjum

“I Built the First self sustaining base in Rust…” by Willjum

“I Built the Greatest Solo Castle you’ll ever see in Rust…” by Willjum

“When a Solo builder and a PVP Chad play Vanilla Rust…” by Willjum

“Overnight on Moldova’s Worst Sleeper Train” by Simon Wilson

“I Tried a Luxury Vietnam Sleeper Train” by Simon Wilson

“I Tested America’s Worst 1-Star Airlines” by Simon Wilson

“I Tried The Worst Sleeper Train in Europe” by Simon Wilson

“First Class on Luxury Arctic Cruise” by Simon Wilson

“Overnight in the World’s First Ice Hotel (Arctic Circle)” by Simon Wilson

“I Flew To The Northernmost Town On Earth (North Pole)” by Simon Wilson

“Cheapest vs. Most Expensive vs. Homemade Fish Sandwich” by Mythical Kitchen

“Cheapest vs. Most Expensive vs. Homemade Cooking Challenge” by Mythical Kitchen

“The Deadliest Total War Campaign Ever Played” by More Warpstone

“Skyrim Speedrun, but the quests make no sense” by DougDoug

“The Absolute Chaos of Bethesda” by big boss

“The Absolute Chaos of Concord” by big boss

“Nikola Motors | The Future of Transport” by big boss

“GTA 5’s most chaotic mod, but if I break the law I explode” by DougDoug

“Planet Coaster, but a random disaster happens every 5 minutes” by DougDoug

“The Skyrim Speedrun where you literally just get married” by DougDougDoug

“This Fallout 4 Mod Obliterated my Sanity” by Joov

“Playing my favorite Games ever (and a few that I hate)” by DougDougDoug

“Twitch Chat and I invaded USA with Artificial Intelligence” by DougDoug

“I let Twitch Chat make their own D&D campaign” by DougDoug

“Crazy RPG logic compilation #52” by Viva La Dirt League

“They Made British Fallout and it’s Fantastic” by Joov

“The Hardest Soulslike” by videogamedunkey

“Fake Bear Trap Camping” by Steve Wallis

“40 Best Indie & AA Games You Simply Must Experience” by gamewise

“20 Underrated Open World Games You NEED to Give a Chance” by Pixel Dragon

“I Played 20 Survival Games For 2 Hours Each to Find The Best” by JGigs

“50 Greatest Open-World Games You Can Play Right Now” by Pixel Dragon

“The Most Hated Politician in America” by big boss

“The Most Hated Mayor in America” by big boss

“The Fake Cash Giveaways of McDonald’s Monopoly” by The Fool

“I ran unethical social experiments on Twitch Chat” by DougDoug

“Forgotten Hot Drinks Of History” by Townsends

“I Played 20 FREE RPGs For 2 Hours Each to Find The Best” by JGigs

“I Played 20 Zombie Games For 2 Hours Each to Find The Best” by JGigs

“I flew back to Chennai to EAT!!” by Chris Lewis

“India’s $2.7 Billion Capital Project Explained” by neo

BONUS: EVERY PODCAST EPISODE I LISTENED TO FOR THE FIRST TIME IN 2025

“Nicholas Hoult” by Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend

“Danny McBride” by Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend

“Christina Ricci” by Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend

“Nathan Lane” by Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend

“Bill Hader Returns Again” by Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend

“Diego Luna” by Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend

“Ayo Edebiri” by Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend

“Andy Samberg” by Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend

“Janelle James” by Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend

“Werner Herzog Returns” by Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend

“Rose Byrne” by Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend

“Mary, Queen of Scots: Birth of a Legend (Part 1)” by The Rest Is History

“Mary, Queen of Scots: The Royal Rivals (Part 2)” by The Rest Is History

“Mary, Queen of Scots: The Battle for Scotland (Part 3)” by The Rest Is History

“Mary, Queen of Scots: Murder Most Foul (Part 4)” by The Rest Is History

“Mary, Queen of Scots: The Mystery of the Exploding Mansion (Part 5)” by The Rest Is History

“Mary, Queen of Scots: Downfall (Part 6)” by The Rest Is History

“Peter the Great: The Rise of Russia (Part 1)” by The Rest Is History

“Peter the Great: Bloodbath in the Kremlin (Part 2)” by The Rest Is History

“The Great Northern War: The Battle of the Baltic (Part 1)” by The Rest Is History

“The Great Northern War: Revenge of the Cossacks (Part 2)” by The Rest Is History

“The Great Northern War: Slaughter on the Steppes (Part 3)” by The Rest Is History

“The Great Northern War: Murder in Moscow (Part 4)” by The Rest Is History

“Rasputin” by The Rest Is History

“The First World War: The Invasion of Belgium (Part 1)” by The Rest Is History

“The First World War: The Battle of the Frontiers (Part 2)” by The Rest Is History

“The First World War: The Miracle on the Marne (Part 3)” by The Rest Is History

“The First World War: The Massacre of the Innocents (Part 4)” by The Rest Is History

“The First World War: The Eastern Front Explodes (Part 5)” by The Rest Is History

“The First World War: Downfall of the Habsburgs (Part 6)” by The Rest Is History

“Elizabeth I: The Fall of the Axe (Part 1)” by The Rest Is History

“Elizabeth I: Anne Boleyn’s Bastard (Part 2)” by The Rest Is History

“Elizabeth I: The Shadow of the Tower (Part 3)” by The Rest Is History

“Elizabeth I: The Virgin Queen (Part 4)” by The Rest Is History

“Judd Apatow Returns” by Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend

“Quantum Refuge” by Radiolab

“Hundred Years’ War: Henry V’s Invasion of France (Part 1)” by The Rest Is History

“Hundred Years’ War: The Road to Agincourt (Part 2)” by The Rest Is History

“Hundred Years’ War: Bloodbath at Agincourt (Part 3)” by The Rest Is History

“Hundred Years’ War: England Triumphant (Part 4)” by The Rest Is History

“Will Arnett Returns” by Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend

“Hannibal: Rome’s Greatest Enemy (Part 1)” by The Rest Is History

“Hannibal: Elephants Cross the Alps (Part 2)” by The Rest Is History

“Hannibal: The Invasion of Italy (Part 3)” by The Rest Is History

“Hannibal: Roman Bloodbath at Cannae (Part 4)” by The Rest Is History

“Custer vs. Crazy Horse: Civil War (Part 1)” by The Rest Is History

“Custer vs. Crazy Horse: The Winning of the West (Part 2)” by The Rest Is History

“Custer vs. Crazy Horse: Horse-Lords of the Plains (Part 3)” by The Rest Is History

“Custer vs. Crazy Horse: Rise of Sitting Bull (Part 4)” by The Rest Is History

Read more at BenBoruff.com.