Recently, this post popped into my feed: “Normalize not bringing up a relatable story about yourself when someone is telling you something about themselves, and just listen.”

I didn’t think much about it, to be honest. It seemed reasonable to me. Sometimes, folks want to be heard, and—sometimes—feeling heard requires the listener to focus on the speaker’s experience (as opposed to their own).

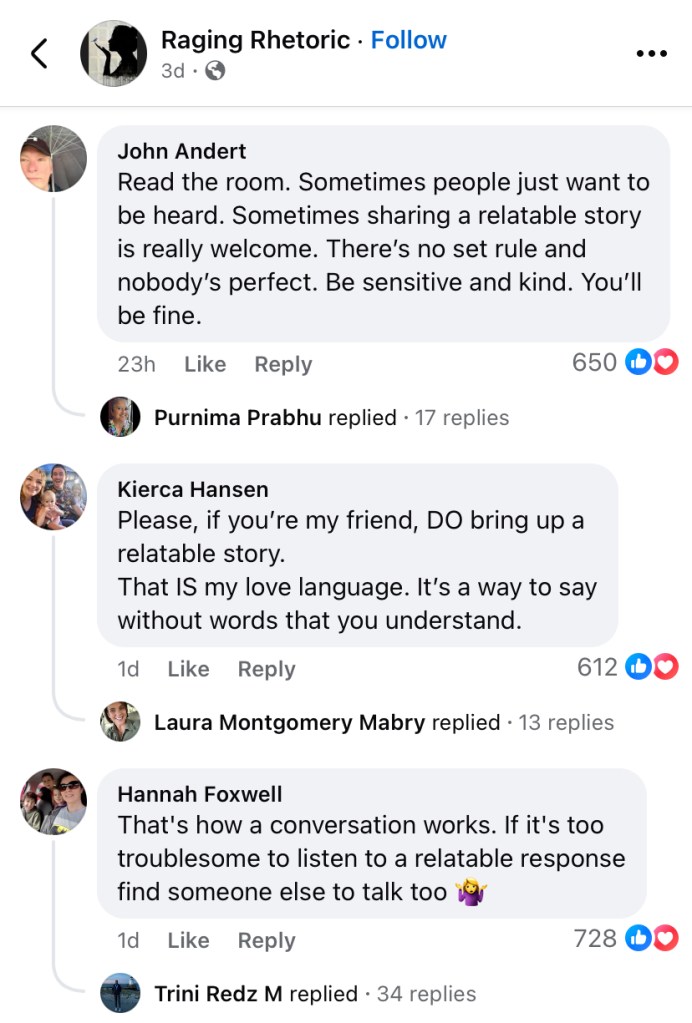

But then I read some of the comments.

There is much to unpack in these comments, including a few logical fallacies and some arguably misguided assertions about neurodiversity. But what surprised me was the widespread indignation of the commenters. The spirit of the comments is valid: vocalizing shared experience can be a way to empathize and deepen conversations. And, yes, active listening does not require silence on the part of the listener. But those elements were not the focus of the original post. The original post simply asked would-be listeners to spend time focusing on the speaker’s experience before pivoting to their own.

And some commenters couldn’t handle that.

The “Share a Similar Story method,” as one commenter described it, is a feature of empathy, not necessarily active listening, and it can feel dismissive to the speaker. Consider the snow globe analogy from Mae Martin’s stand-up special:

Okay, this is a little abstract, but don’t you think, in a way, our brains and our minds are like our rooms, and we furnish our minds with experiences that we collect to then build what we think of as our identity and selves? And that’s all we’re doing. We’re little experience hunters, collecting these to put them on our brain shelves and be like, “I’m me.” And I always visualize every experience that we collect is like a little novelty snow globe. We’re just going around, being like, “One time I saw Antonio Banderas at the airport. Yes, I did. I’m myself. And no one else is me.” And then all human interaction is . . . just basically taking turns showing each other our snow globes. And being like, “I…” And just pathetically taking turns. And, like, someone will be showing you their snow globe, you know, and you’re trying to be a good listener. It’s a story about a party they went to five years ago. And you’re like, “Yes, and you are you as well.” Like, “Yes, exactly, yes.” “How wonderful to be yourself as well.” But the whole time, your eyes are darting to your own shelf. A hundred percent, the whole time… You’re like, “Mmm, yes. Well, no. Yes.” Waiting for your moment to be like, “And me as well. I have one…”

Sometimes, effective listening requires sacrifice. Sometimes, to truly hear and appreciate the experiences of another person, a listener must abandon the temptation to match those experiences with their own—at least for a little while. While listening to another person, instead of searching your head for your own experience (AKA your snow globe), you could actively listen to (and comment on) the experience presented by the speaker.

For many people, effective listening is not the status quo. In fact, I argue that most people are bad listeners—a reality perpetuated by casual egotism and a widespread tendency to instinctively personalize the stories of others. In a video essay about Noah Baumbach’s 2017 film The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected), YouTuber Nerdwriter uses the film to examine the reality of day-to-day conversations. At one point, Nerdwriter dissects a scene between Matt (played by Ben Stiller) and his father Harold (played by Dustin Hoffman):

. . . What makes this exchange so heartbreaking and true to life, at least for me, is that they really are communicating with each other—just not explicitly. Matt brings up a major life change and expresses some of the hopes and fears he has about it, and his father immediately brings up his own major life event and some of the hopes and fears he has about that. Implicitly, Matt is asking for approval, he’s asking for reassurance, and he’s asking for consolation. Harold, on the other hand, is denying approval because he can’t his son being more successful than he is, while asking for reassurance of his own hopes and consolation for his own fears. It’s like the two men are firing a volley of missiles at each other: some are hitting, some are missing, and some are crashing into each other midair. I think Baumbach understands a key dynamic in conversations, especially conversations with family: When we speak to others, we’re often speaking to ourselves, attempting to frame dialogue so that the person we’re talking to will reflect back the things that we want to believe about us. . . . And the result is often conflict or a conversation that just goes nowhere.

Ultimately, much of this issue comes down to the nuances of specific conversations. If, for example, I quickly mention the fact that I have experienced depression as a way to establish a connection with someone who has just shared a story of their experiences with a recent depressive episode, I am showing empathy. If, however, I respond to my friend’s story about their depressive episode with an unsolicited story about my mental health, I am no longer just showing empathy—I am hijacking their moment to highlight my own experience.

The line between empathizing and commandeering is sometimes tricky to see, especially for those with notably solipsistic tendencies. Listeners must quickly consider a number of contextual variables: level of familiarity, the emotional disposition of the speaker, power dynamics, physical location, and more. If “reading the room” was easy, miscommunications and hurt feelings would never occur. But they do occur. Frequently, in fact. Which means that some of us are not as good at listening as we assume we are.

So let’s look at examples of obviously ineffective listening and fine-tune our approach from there. When arguments occur, we often demand understanding through tone and volume. During an argument, the struggle to feel heard often manifests as vocalized frustration: we shout to keep the other person from overlooking our perspective. Consider the flawed styles of communication in movies like Sam Mendes’s Revolutionary Road, Noah Baumbach’s Marriage Story, and Justine Triet’s Anatomy of a Fall.

In all three cases, the characters shout their feelings and experiences at each other, and they do so without earnest attempts to appreciate perspectives beyond their own. Most individuals, I imagine, would agree that these cinematic conversations exemplify a failure of effective communication. In these scenes, much is communicated, but little is understood. It’s easy to look at arguments and see the dangers of selfish exchanges. But self-centeredness is not limited to heated arguments: the clearly ineffective elements of hostile communication—the chaotic drive to be heard and the self-focused tendency to personalize the experiences of others—can also exist in casual, non-hostile conversations. They’re just more subtle.

My contention is that when attempts at empathetic “listening” are driven primarily by a desire to verbalize relatable experiences, those attempts often suffer from the same pitfalls as the arguments in Anatomy of a Fall—just maybe to a lesser degree. In both situations, understanding is overshadowed by verbalized personal experience. In the mind of the speaker, it is not clear if the listener has truly internalized what was said.

Let’s use Fences, the 2016 film adaptation of August Wilson’s play, as a case study. Troy Maxson (played by Denzel Washington) is a toxically masculine father who cheats on his wife Rose Maxson (played by Viola Davis). Like Willy Loman from Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, Troy is a problematic communicator: he has a notably tunnel-visioned view of the world that informs everything he says. Every comment or reply is filtered through a limited lens of baseball references and unyielding personal philosophies.

At the beginning of a pivotal scene, Troy tells Rose that he has fathered a baby with another woman, and this admission sparks a conversation about their marriage. Rose is understandably frustrated, and she explains that Troy should have “held her tight,” regardless of any emotional distance between them. Then Troy’s language shifts: he tries to explain his perspective through a series of baseball metaphors (“I bunted” and “I wasn’t gonna get that last strike” and “I wanted to steal second” and “I stood on first base for eighteen years”). Troy makes little attempt to empathize with Rose; instead, he insists on framing the conversation in a way that makes sense to him. He insists on language that reinforces his experience, not hers. (And, intriguingly, Troy actually accuses Rose of “not listening.” Sometimes, the most thunderous among us are the quickest to feel unheard.)

Finally, Rose yells, “We’re not talking about baseball! We’re talking about you going off to lay in bed with another woman—and then bring it home to me. That’s what we’re talking about. We’re not talking about no baseball.”

Now imagine that Troy is one of Rose’s friends, not her husband. Imagine that Rose is talking to a friend about her interactions with her adulterous husband, and Rose’s well-intentioned friend responds with a litany of baseball analogies. Would you describe that friend as an effective listener?

Now replace those baseball analogies with the “Share a Similar Story method.” Imagine that Rose is sharing her experiences, and her well-intentioned friend pivots to their own experience with an unfaithful partner. Would “effective listener” be an appropriate label for that friend?

Sometimes, effective listening requires sacrifice. Sometimes, as a listener, it’s not about you, and quickly pivoting to your experience—even if well-intentioned—feels self-serving. You may not mean to dominate or personalize the conversation, but impressions impact feelings more than intentions.

I believe that genuinely listening to another human being can change that person’s life. All human beings want to feel heard. All human beings crave the feeling of safety, sanity, and comfort that comes from knowing that another person truly heard, appreciated, and validated what they had to say. So when you have the opportunity to offer that to someone else, remind yourself that this is their life-changing moment, not yours.

Ben Boruff is a co-founder of Big B and Mo’ Money. Read more at BenBoruff.com.