Don Delillo’s Cosmopolis is a vexingly slow-paced and pedantic critique of capitalism told from the perspective of a 28-year-old multi-billionaire as he rides in his high-tech limousine through downtown Manhattan to get a haircut. The protagonist’s journey is peppered with visits from business associates and high-level employees, including his “chief of theory” Vija Kinski.

In one scene, Kinski offers the multi-billionaire some advice on the nature of wealth:

The concept of property is changing by the day, by the hour. The enormous expenditures that people make for land and houses and boats and planes. This has nothing to do with traditional self-assurances, okay. Property is no longer about power, personality and command. It’s not about vulgar display or tasteful display. Because it no longer has weight or shape. The only thing that matters is the price you pay. Yourself, Eric, think. What did you buy for your one hundred and four million dollars? Not dozens of rooms, incomparable views, private elevators. Not the rotating bedroom and computerized bed. Not the swimming pool or the shark. Was it air rights? The regulating sensors and software? Not the mirrors that tell you how you feel when you look at yourself in the morning. You paid the money for the number itself. One hundred and four million. This is what you bought. And it’s worth it. The number justifies itself.

For the super-rich, the value of wealth eventually transcends money. $20 billion. $50 billion. $100 billion. $5 quintillion. What does it matter? Because at some point, everything becomes accessible, so the act of acquiring feels less like a purchase and more like a gesture—a reminder of the fact that you can. A symbol of one’s transcendence from practical consumption to something else entirely.

Consider Chef Raffaele Ronca’s $5,000 cheesecake.

When I mention this dessert—which contains freshly imported vanilla beans and three shots of a 200-year-old cognac that costs $2,500 a bottle—to my high school students, they respond with understandable questions: Does it even taste good? Is it better than the Cheesecake Factory? Is it worth $5,000?

But those questions miss the point, right?

No cheesecake is worth $5,000. But the taste of the cheesecake is not the point. Even if the cheesecake tastes wildly better than its affordable counterparts, the taste of the cheesecake is still not the point. The exclusivity is the point. Chef Raffaele Ronca is not creating a culinary experience: he’s creating a conditional experience—and the condition is that you have $5,000 to casually spend on dessert one evening. And if you do have $5,000 to spend on a fairly small, one-time experience, then “spending” isn’t really the right word. It’s not a purchase in the same way that a family purchases a car or a student purchases pencils or a mother purchases baby clothes. If the cheesecake had a price tag of $10,000 or $20,000 or $100,000, some wealthy foodies would still buy it. Because it’s not about the taste or the ingredients. Because the act of acquiring the cheesecake is the victory. Because, as Vija Kinski says, “The number justifies itself.”

And this dynamic—the gap between extreme wealth and the rest of us—is part of my problem with Shark Tank.

An official ABC description of Shark Tank describes it as a “business-themed unscripted series that celebrates entrepreneurship in America.” Shark Tank is labelled as a “culturally defining series” that gives “people from all walks of life the chance to chase the American dream and potentially secure business deals that could make them millionaires.” And the producers promise radical change for individual entrepreneurs: “Whichever way the wheeling and dealing may go, many people’s lives will be better off – because they dared to enter the unpredictable waters of the Shark Tank.”

But Shark Tank is, ultimately, just a televised ode to capitalism and wealth disparity. Shark Tank is to American capitalism what the Hunger Games are to Panem’s violent social hierarchy.

Consider the basic premise of Shark Tank: a group of wealthy investors—Mark Cuban ($6.86 billion net worth in 2024), Kevin O’Leary ($400 million), Daymond John ($350 Million), Robert Herjavec ($300 million), Lori Grenier ($150 million), and Barbara Corcoran ($100 million)—hear pitches from entrepreneurs and decide in real time whether or not to invest. Shark Tank viewers are reminded every episode that the investors use their own money to make deals with entrepreneurs, meaning that the handshake deals made on the show presumably lead to legally binding contracts (at least some of the time) in which one or more multi-millionaires join the companies as stakeholders.

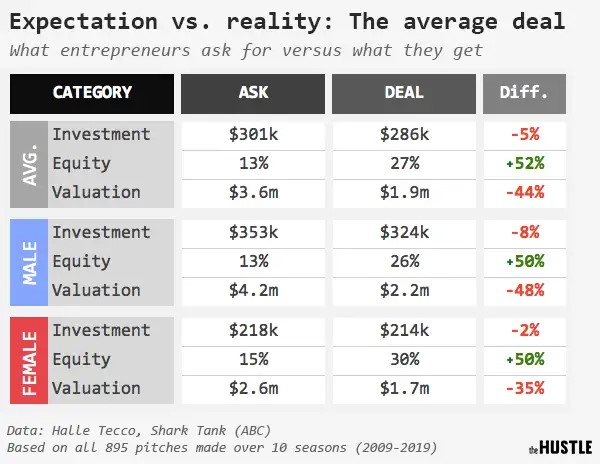

These deals lead to real money, and the investors benefit. In its first ten seasons, Shark Tank had “222 episodes, 895 pitches, 499 deals, $143.8m worth of invested capital, and nearly $1B in company valuations.” And as of 2023, the top eight successful products that received deals from Shark Tank investors earned a combined $1.2 billion in sales. The seven products that received deals during their episodes—Robert Herjavec invested in the Bouqs three years after the company appeared on Shark Tank—were offered an average of a $157,000 investment in exchange for an average stake of 18.9% in the company. (Not to mentioned that each Shark is paid approximately $50,000 per episode.)

The only individuals to consistently benefit from the show are the Sharks, so Shark Tank is really about rich folks getting richer. The Sharks undoubtedly profit off of their investments, and they do so while helping only a small handful of entrepreneurs with their businesses. A Forbes analysis of Shark Tank highlighted the frequency of deals dying after the credits roll: “. . . an analysis of 112 businesses offered deals on seasons 8 through 13 of the show reveals that roughly half those deals never close and another 15% end up with different terms once the cameras are turned off.” Here, the mirage of a good-natured show where “many people’s lives will be better off” begins to fade.

Shark Tank is a spectacle in which the wealthy profit off of the ideas of the non-wealthy, and the rich investors are portrayed as heroes for bothering to show up.

The show bottles capitalism in its most unregulated form—get money however and whenever possible—and sells it raw. “Ambition,” “power,” and “social mobility” in big letters on the package.

That’s the appeal.

Shark Tank is entertaining as hell because of its unapologetically glossy portrayal of American ambition and greed. It’s The Kardashians with investment portfolios. It’s Bling Empire with equity negotiations. It’s Billions without Paul Giamatti. Shark Tank is about the Sharks, not the entrepreneurs, because many middle-class Americans watch shows about wealthy Americans for some of the same reasons we watch documentaries about serial killers: we want to stare at the “other,” the person who is distinctly not us—but who, with a couple fantastical twists of fate, could be us. We are morbidly fascinated by the person for whom property “no longer has weight or shape” due to their extravagant wealth.

The Sharks, like the customers of Chef Raffaele Ronca, are playing a different game than the show presents. This is not a show of veteran entrepreneurs helping new entrepreneurs; no, Shark Tank is a show about the super-rich playing with the lives of non-rich individuals. For most of the guests who pitch their ideas, receiving $50,000 to $500,000 would be world-changing. For most of the Sharks, that money is nothing. It’s a number that yields a result. It has little practical value beyond the impact it has on the narrative of the episode, which is both the appeal and the problem of the show.

Shark Tank is troublesome because the show’s editing and advertising paint a picture of gallant investors who have agreed to bless normal folks with their advice, but the show is just a machine designed to benefit the rich judges—both financially and reputationally. American Idol has a similar gimmick, but American Idol is less problematic because 1) an American Idol judge’s personal wealth is not a fundamental element of the show and 2) American Idol has not made a spectacle of a weighty and often closed-door financial proposition. Singing competitions are inherently spectacular; data-oriented investment pitches are not.

Imagine a reality show in which cameras followed families as they applied for personal loans. We’d hear their stories, and we listen to the suit-and-tie bankers as they weighed the potential risk of approving loans for certain families. Sometimes, the banker would discover a flaw in the family’s application—unstable income or a wavering credit score due to medical debt—and the well-dressed banker would admonish the family for their sloppiness before stamping “DENIED” on their paper. I imagine the show would be called something simple and alliterative like Bank or Bust.

Shark Tank is more Bank or Bust than it is American Idol.

For the super-rich, the value of wealth eventually transcends money. So watching Kevin O’Leary mock a low-budget entrepreneur from Ohio feels icky. It’s punching down in its worst form. It’s the opposite of eating the rich: Shark Tank—as its name implies—is about the rich eating you.

It’s human nature, I suppose, to be intrigued by shark attacks. What’s weird is when we start rooting for the sharks.

Ben Boruff is a co-founder of Big B and Mo’ Money. Read more at BenBoruff.com.